1. Changing the Grammar of the Game

Editor’s note:

the original interview was published on 17th August, 2010.

I’d like to discuss the system side of The Last Story today with Sakaguchi-san and Matsumoto-san from AQ Interactive1, who worked from the start of the project. 1 AQ Interactive was a Japanese game development company. In 2011, it merged with Marvelous Entertainment to become Marvelous AQL Inc.

It’s a pleasure to join you today. I was responsible for system development on The Last Story. I worked alongside Sakaguchi-san on Blue Dragon2 and have continued to work with him for the last seven and a half years. 2 Blue Dragon is an RPG released in Japan in December 2006. It was developed by Mistwalker and Artoon, who later became AQ Interactive.

I’d like to begin by asking you both to tell me how the The Last Story project originally got under way?

Well, it began with me coming up with a planning document for the game. Then, around the same period, I met Matsumoto-san for a drink in Daikanyama in Tokyo, and we discussed the state of video games. I’d say that’s when it all started, wasn’t it?

Yes, that’s right. It was during that discussion that we realised that we had quite similar ideas about the problems and issues facing games.

Our main focus was on the lessons we felt we had to learn from Blue Dragon, a game we had made together. For a start, there was the fact that the game had not been embraced by European or US players. Then we discussed the difference between Japanese audiences and consumers in the West. Judging from the reaction of players to our games, we came to the conclusion that we may have chosen a relatively easy path by making too many games in the same style.

So your shared ideas of the problems with your approach up to that point became the starting point for working together on The Last Story

Yes, I think you could say that. We talked about the innovative games of the time, and it just so happened that we had both been watching the same clips on a video-sharing site.

Yes, that’s right.

We’d both been watching footage of a certain game, and it had come as a real shock to us. It seemed to be a game with a completely fresh approach, and we both had exactly the same reaction: ‘Why didn’t I think of that?’

We were really kicking ourselves...

Right. Our job is to surprise our audience, after all. So when a game comes along that really astounds you, for someone creative, it’s not something you can take lightly.

Right, there’s a very particular kind of pain you feel.

It was at the end of this discussion that we vowed we would come up with a new approach, and we would do it soon. That’s what spurred us on to create the prototype, ‘Tofu-kun’3.

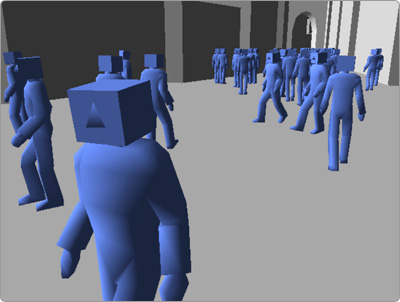

3 Tofu-kun was a prototype created for the purpose of developing The Last Story system. The ‘tofu’ is a reference to the heads of the characters, which resembled blocks of tofu.

Before creating the graphics for the game, we looked at how all the elements in the game would function and fit together. From beginning to end, we probably spent about a year working on ‘Tofu-kun’.

Matsumoto-san, what was your initial take on the new approach Sakaguchi-san wanted to take for this game?

Well, I knew that we would have to come up with a new battle system. I knew that if we didn’t change the grammar of the game, we would end up endlessly repeating the same thing. That’s how we ended up creating a prototype featuring a hero and three companions with blue blocks of tofu for heads, along with red tofu enemies.

We even gave the enemy leader a pair of red spectacles.

You put a pair of spectacles on a block of tofu?

Yes, we did! (laughs) Those blocks of red and blue tofu became our basis for a process of trial and error. In the prototype, we made it so you could turn your attention to the leader, giving the player the choice to focus their fire on him. They could then order their allies to prioritise this, which ended up forming the core of the final battle system.

The other thing we discussed that night was how important it was to get the collision detection right. This refers to creating those things the player can touch and feel and interact with. We placed a lot of importance on giving the player the sense that the character they were controlling interacted smoothly with the surface they were running on. This included things like the player character concealing themselves in the shadows, and squeezing themselves into tight gaps and through alleys. We wanted to allow the player to interact with all sorts of areas of a complex and varied terrain.

We were determined to make it so objects that are usually only treated as background decoration could be interacted with. We designed levels that would allow you to enjoy playing with the terrain, such as climbing walls and hiding in gaps. Level design4 was inextricably bound up with the creation of the landscape of the game. We dedicated a considerable amount of time to that from the start. My task became finding a way to fit the story that Sakaguchi-san had created into the terrain of the game. 4 Level design refers to the creation of each level’s environment and terrain, together with adjustment of the difficulty level.

Could you explain what you mean by fitting the story into the terrain of the game?

Matsumoto-san would determine the actions and casual conversations between characters inside dungeons. The story for the game was created in three stages. The first stage was the overarching narrative, which I came up with. Then there was the interaction between the characters inside the dungeons in the game. Then finally, there were the lines that the director added.

For example, a character might take a tumble, and another character might laugh at them. We added all sorts of exchanges like that.

So you thought about the way the story would utilise the stage upon which it was set, and fit it into the terrain accordingly.

Yes. Let’s take as an example a dungeon where your companion Yurick is at the centre of the action. We have made a situation within the dungeon map where he acts alone. By doing that, we can highlight the fact that he hasn’t yet opened up to his companions and fully accepted them.

To what degree do ideas like that come from you, Sakaguchi-san, and to what degree are they additions made by Matsumoto-san?

I came up with the broad plot, and there were times when I would look at the game’s terrain and suggest events that might occur.

So I take it you had never worked on a project where the events in the game were so intimately bound up with the level design.

True. This was the first time for me.

I think most people picture you coming up with the story along with an image of the world you want to create, and then others come up with graphics and gameplay that reflect that vision. But The Last Story was developed in a completely different way. I imagine that people reading this interview will be really taken aback by this.

Well, the team may have got a little carried away at times... (laughs)

Right. Sakaguchi-san did lose his temper with us six or seven times. (laughs) He’d say things like: ‘Yurick wouldn’t do that!’

But I’m sure there are important elements in the game that wouldn’t be there if the team hadn’t got slightly carried away.

Yes, that’s true. There were ideas that the team put in to get attention or cause a stir which ended up being used in the final game.

That’s right. Take the hero, Zael, for instance. He’ll always open doors by kicking them, and his companion will respond by saying: ‘There you go, kicking down doors again!’ At first, that was just a joke, but then people started saying it was a great feature. That’s why we ended up leaving it in the game as one of that character’s distinctive traits. There are a lot of elements in the game that originated with Matsumoto-san.

And then there’s Zael’s poor sense of smell.

That’s right. Zael doesn’t have much of a sense of smell. You’ll have scenes where he’ll be near a really malodorous monster and be baffled at everyone else’s reactions. Then his companion will make a joke about how lucky Zael is... (laughs)

It feels really funny to have that kind of conversation going on inside a dungeon.

Right. Those exchanges create a particular feel or atmosphere, and I think it’s great that you’ll find that running right through the game.

So you had a process where the staff would come up with ideas and exchange opinions about what should and shouldn’t happen, and this has all ended up combining to create the unique feel that the game world has.

That’s right. I think there’s a kind of vitality that you’ll find whether you’re in the dungeons or the town. And I think that the reason we’ve ended up with that is precisely because this vitality wasn’t planned for from the start... Hmmm, how should I put it...?

Well, that manifests itself as a particular feel that runs through the game. I mean, the real world is such a mix of different elements that you could never hope to capture a sense of realism if just one person was trying to come up with it all.

That’s right. I think this unique feel that the game has was something born out of Matsumoto-san and the way he interacted with the whole team.

And I think that it’s because you were open to these ideas that we were able to implement a lot of them in the game.

Well, you just can’t plan details such as a hero who opens doors by kicking them right from the start. I think that all kinds of interesting aspects of the characters’ personalities came out of those conversations inspired by the level design. That’s something that you can’t predict until the process is in motion.

With the action in the dungeons played out in real time, the speed the characters walk at and the way they joke and interact becomes really important.

To be sure, the feel of a dungeon won’t come simply from its sheer size, but also from the speed the characters move at, and the points at which events occur.

In this game, it was really brought home to me once again how the feeling of realism and vitality in a dungeon is born out of the events that unfold there and the interactions the characters have within it.