Page 3

Okay, so that concludes the introduction to my game development history and now I’d like to turn to today’s topic.

Why is it that someone like me is standing up here? What was it that Mr. Iwata was wondering about?

Actually Mr. Iwata was curious about my game development methods and this led me to the theme of the speech I’d like to make today.

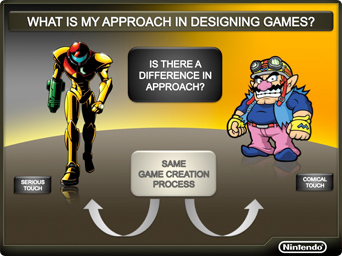

Mr. Iwata was curious about how one person could work on a serious game with an involved story like “METROID: Other M” and at the same time work on comical and eccentric titles like “TOMODACHI COLLECTION” and “WarioWare: D.I.Y.” He was looking for an explanation as to what my stance was and what my approach was when creating games that are completely opposite.

“Exploring the secret of creating games for such a dynamic range of titles should lead to something interesting. Why don’t you talk about this at GDC?”...

When Mr Iwata suggested this to me, I found myself slightly perplexed, mostly because I had never actively thought about it.

It’s true that the styles are completely different. That’s something that people have said to me a number of times. What was my approach as producer on each of those titles? And what does it mean to be a producer in the first place? Having actively thought about it, I discovered what a hard question it is to answer. I’m not particularly good at applying logic to intuitive actions but given this opportunity… I decided to analyse “my own ideas on game creation.”

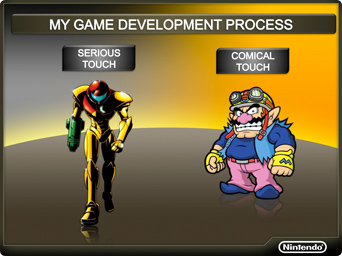

Okay, so for the sake of explanation, I’d like to give names to these games of differing types – I will call METROID-type games “serious” and Wario-type games “comical.” By the way, Mr. Iwata doesn’t find it odd that I’m able to negotiate working on polar opposite “serious” and “comical” type projects, rather it’s that he finds it puzzling that I can create something with a “serious touch” at all. I am well aware that Mr. Iwata thinks of me only as “someone with the comical touch.”

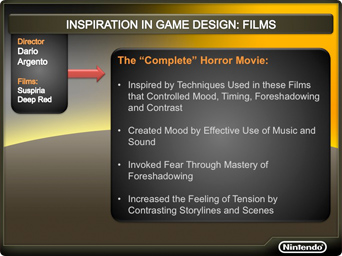

I’d like to take a moment to talk about one film director that I came across in my youth. His name is Dario Argento17 and he is an Italian film maker. He is most well-known for his films, Suspiria18, and Deep Red19. Without a doubt, Deep Red has had the greatest inspiration on my creative process. I’d always been interested in scary movies, but at the time, there wasn’t one that I could really get behind. I always felt some frustration as they’d leave me feeling that “there was just something missing” about them. That is until I came across Argento’s films. I was really taken aback by the originality of his technique. The style that I’d been looking for all along was there. I discovered that without a doubt, I wanted to create things in the manner like Argento did. This is how I understood the components of his technique.

17 Dario Argento is an Italian film director who has been involved with numerous horror films.

18 Suspiria was a horror film released in 1977. It became known for its tagline (translated from Japanese) ‘’Be sure not to watch it alone’

19 Deep Red was released in 1978 in Japan, and was marketed there as ‘Suspiria Part 2’.

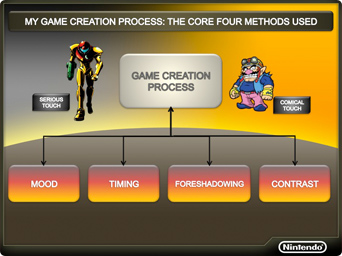

A creator can control the “mood,” ”timing,” ”foreshadowing,” and “contrast” to scare his audience. “Mood” can be set by the music one chooses. The music Argento used was progressive rock20. The almost indifferent echo of the stiff and robotic progressive rock sound directly brings out that feeling of terror in the audience and is far more effective than the music used in any other horror movie. And Argento effectively stopped the music at very specific moments in his scenes and did things like using sound effects to change the mood.

20 Progressive Rock is a genre of rock music that originated mainly from the UK in the late 1960s. It adopts elements of classical and jazz music and uses complex compositions and phrasings.

Also, he was meticulous about using certain tricks to increase the feeling of fear. In other words, he was a master of using “foreshadowing” to connect events to one another effectively.

And he contrasted storylines and scenes dramatically to increase the feeling of tension. Having had my sensitivity stimulated so strongly by the works of Argento in my youth, I’ve had opportunities to reflect these inspirations in my work. On the aforementioned “Famicom Detective Club Part II, the Girl Standing Behind,” I controlled the mood, timing, foreshadowing, and contrast. In other words, this title was my homage to Argento’s work.

This experience allowed me to gain confidence in my own ability to effectively produce a game, and I continued to use this approach on the titles that followed. My latest project, “METROID: Other M” is no exception.

This technique of controlling mood, timing, foreshadowing, and contrast that I have relied on throughout my career as a game designer, I realised early on, isn’t anything special or different at all. Nonetheless, the reason I am sharing this is to show you how deep my desire was to find the ideal method of conveying fear and how that led me to find my own creative style. I was reminded of that fact in writing this speech. Having found my own sensibility and creative style, I can’t help but want to pass that on to someone else.

After having seen Argento’s films, I started watching a lot of movies. I was looking for a variety of ways to control mood, timing, foreshadowing, and contrast, and not just in horror movies. I watched many different types of films. I discovered that there are a number of hints hidden in cult movies as well. I think it was at this time that my ability to create images in my head - you might even say daydream - became stronger. It might sound like a joke, but I started to have dreams viewed from an objective point of view, with edited scenes and their own background music. At the time I was hungry for a good movie, but I wasn’t drawn to big Hollywood productions. And that feeling is even stronger now. Maybe my affinity for niche things extends even beyond games?

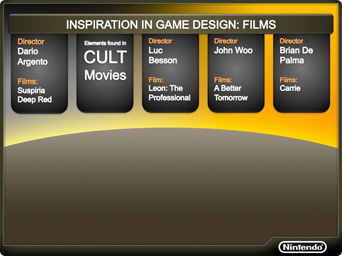

By the way, here are a few other directors and movies that I was inspired by. I also found inspiration in the films of France’s Luc Besson21. I really appreciate his ability to depict sorrow as something deep and beautiful. My favourite Besson film is “Léon: The Professional.”22 Another director I love is John Woo23, who is currently active in Hollywood. Woo’s films from the “A Better Tomorrow”24 series, which he created when he was working in Hong Kong, had a particular effect on me. The sorrow that oozes from the mayhem he creates is magnificent. There was much for me to learn from the almost painful images coming out of the Hong Kong movie scene at that time. I was also inspired by Brian De Palma25. The intense last scene in Carrie26 served as a significant guidepost for me.

21 Luc Besson is a French film director responsible for creating films such as Léon and The Transporter.

22 Léon was an action movie released in 1995, starring Jean Reno and Natalie Portman.

23 John Woo is a Chinese film director responsible for titles such as Face/Off, Mission Impossible 2 and Red Cliff.

24 A Better Tomorrow was an action movie released in 1987, starring Ti Lung and Chow Yun-fat. It was directed by John Woo.

25 Brian de Palma is an American film director responsible for titles such as Scarface, The Untouchables and Mission Impossible.

26 Carrie is a 1977 film adaptation of a Stephen King horror novel. It was directed by Brian de Palma.

Let me add one more thing about movies. I’ve seen many movies and been moved by them in many ways, but I’m not a movie fanatic. I haven’t seen every movie that the aforementioned directors have made, and I haven’t seen any more movies than the average person. I have great admiration for these directors but it’s not as though I’ve got a complex about it or that I strive to become one. It’s just that I was inspired and moved by their films and that has inspired the way I create games. They’ve helped bring that out in me.

If I start talking about this, I won’t be able to stop, so I’ll leave it at that. It might sound presumptuous, but I believe that the impact that these great directors have had on me is evident throughout the titles I’ve worked on. I secretly look forward to players noticing these influences when they play “Other M” in the near future.

While I’ve looked to films for inspiration, it’s not as though that’s all that interests me. Among my many hobbies, I have long been an aficionado of music, especially because of how it can be synched with images. Another hobby is one that I’ve had since I was a youngster and continue to have now. That is “comedy.”

I love things that are funny and things that make me laugh. Is there a laugh hidden in here? Can I find something funny in this? I spend much of my day searching in this way. If asked if I want to laugh, of course I would say I do, but actually, I also want to make people laugh. I’m not a comedian though, so I can’t just send a crowd of people into an uproar. I’m just happy to add a little spice to my day and make the people around me have a good time… That’s all I want to do. Saying that might give you the impression that I take all this lightly, but I’m actually quite meticulous about it.

I constantly work to hone my senses and when I find material I can use, I make sure to tuck it away for later. I gather as much varied material as possible – to fit any situation or any audience. However, I make sure that what I keep fits my particular style.

And when it occurs to me, I will take my best material and in my head, simulate the situation in which I would use it in order to find the best delivery. I’ve never thought about why I think it through so far, but having given it some thought in writing this speech, I realised that I want to control audience reaction - I want to engineer the “laugh.”

In addition, ultimately the techniques used are mood, timing, foreshadowing, and contrast. In this case, rather than CREATING a mood for a scene, it’s better to take a read on what sort of mood is already there and give it space to breathe. Timing is so important in comedy; for example, in a group of people, that moment when everyone is quiet – that lull in the conversation – if you miss it, it’s gone forever. Steering a conversation so as to set up the prefect one-liner is like the way an author uses foreshadowing. And it goes without saying how important creating contrast with a sense of urgency is.

I think we’re nearing the core of “what Mr. Iwata finds puzzling about my game-making style.” I feel that my appreciation for comedy and the influence that movies had on me affected my approach toward “comic touch” games and “serious touch” games. To borrow Mr. Iwata’s words, they’re polar-opposite types of games. So, is it that I’ve adopted a particular stance or approach in dealing with them?

Whether serious or comical, I respond strongly to things that stimulate my interest and when I think “I might be able to use it later,” I store this material away and wait for the opportune moment to bring it out. And the methods or strategies in which I employ them are the same – through controlling “mood,” “timing,” “foreshadowing,” and “contrast.”

The experience of thinking something is funny or cool or scary is all the same as having one’s feelings moved. And the mechanism to get someone to that point is all part of the same process, regardless of the type of feeling.

So a developer must think about how the audience’s emotions are moved and control those mechanisms.

And in order to make effective use of this control, one must experience all kinds of things and feel them within their own contexts. Adopting this attitude in day-to-day life will naturally bring in a wide variety of material to pull from.

So in response to Mr. Iwata’s question, I think it can be explained like this: I just happened to be passionate about the serious and the comical – two opposing types – and was really fortunate to be given the opportunities that I have.

So to summarise today’s theme of “what Mr. Iwata finds puzzling about my game-making style”…

What is the difference in stance and approach I take when creating games that are polar opposite types? In response to Mr. Iwata’s question…

The answer is, “There really is no difference in my stance or approach.”

It’s more about technique.

I think this is the real answer.

“As long as one is open to the possibility of new experiences and is willing to feel them deeply, you can use a single toolset to create works that move people’s hearts in a great many different ways.”

I’d like to leave it to you to decide if this is accurate or not.